Learning from Las Vegas

Learning from Las Vegas was a good case study to look at. The book developed for Anne West’s writing workshop dealt with the sign as a building, and how contemporary conception of space involves with signs, information and symbols rather than abstract form. Constructing an interactive book as a means of breaking up the space of the page, I created a book in a flipable form that allows endless variations and juxtapositions of pages and information.

It is really important to look at readings which are relevant to my topic but are also coming from a vocabulary of expression— architecture writing—that I am familiar with. I can reanalyze a lot better if I understand already the history, the background, the theory—all the things that make up the genre of writing. I can look at it with different eyes and see how it applies to my thesis topic. I think this has been a very a specific case study which allowed me to establish specific definitions to analyze oppositions of spaces and buildings.

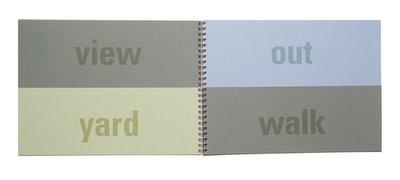

I created a book in which the top and the bottom of the book can be turned at different speeds to create a vertical opposition of two bodies of content: modern architecture and vernacular architecture. Hammett was very intrigued by the reinterpretation of the text in the flipping book format. In this format, the flipping of the pages gives the reader variability and depth. Just as they perceive their surroundings in space, and can approach an isolated point from different sides, from the front or the back or either of the two sides, the flip book allows the reader to approach the book from different perspectives. The pages flip and have variability and depth. The depth and dimension is not frozen in space, but changeable depending on the user’s needs and interests. It is a flat page which has space in it.

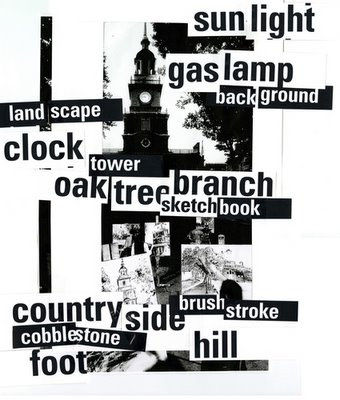

My book has a foreground, middle ground and background. It has depth not just in the variable page sizes, but in the pages that involve overlaps and juxtaposition of transparent letterforms. The juxtaposition of flatness and depth is a relevant topic of study for a book that deals with the content of a two dimensional sign taking the place of a three dimensional building.

The variable quadrants create a different sequence and different story depending on how the book is flipped. I liked the information from Learning from Las Vegas—but the complete quotes tend to get too overwhelming to juxtapose in the four quadrants. Maybe if I go in line by line, word by word, I can start making pairings between lines, and have a reason for juxtaposing the four quadrants together. Right now it is still paragraph by paragraph, the meaning is a bit more ambiguous when you start comparing paragraphs from top to bottom. What if it was a sentence, what if it was a word? That specificity would create a new unified whole from the fragments.

What am I going for when it comes to these fragments? Why would people want to reconstruct them? What do they want to get out of it? I like Hammett’s suggestion—the way I am fragmenting is more framing what I see rather than cutting apart for the sake of cutting apart. It involves the ideology that adding and subtracting allows the user to see something else on the page. The fragmentation has a construction aspect to it. I am trying it out with wax, dots, spray paint, letterpress and transparencies. All are 2D physical mediums but they allow people to have a new reading of the content with their interactivity and variability.